Much of what we think about the world we believe on the basis of what other people say. But is this trust in other people’s testimony justified? This week, we’ll investigate how this question was addressed by two great philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment, David Hume (1711 – 1776) and Thomas Reid (1710 – 1796). Hume and Reid’s dispute about testimony represents a clash between two worldviews that would continue to clash for centuries: a skeptical and often secular worldview, eager to question everything (represented by Hume), and conservative and often religious worldview, keen to defend common sense (represented by Reid).

The Enlightenment was the period in European intellectual history beginning in the late seventeenth century and throughout the eighteenth century, characterised by the revolutions in the field of science, politics, society and philosophy. These revolutions swept away the medieval world-view and ushered in our modern western world. In addition to the French, there was a very significant Scottish Enlightenment (key figures were Francis Hutcheson, David Hume, Adam Smith, and Thomas Reid).

Intellectual Autonomy

Hume is probably most well-known for his naturalistic philosophy. He doesn’t appeal to God or anything supernatural in giving philosophical explanations. He was a sceptic and is noted for his arguments against the cosmological arguments for the existence of God. In his Treatise of Human Nature, he proposed to study human beings with the same experimental scientific method that we use to study the rest of nature.

His article “On Miracles” in “An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding” has also been highly influential. Hume defined miracles as a violation of nature. Hume argues that we have no reason to believe in miracles and should certainly not consider them foundational to religion. We derive our knowledge of miracles only on the testimony of others who claim to have seen them. Since this is a second-hand testimony (experience of others) and not our own experience, we should not rely on it. Hume said that you should only believe people if they are likely to be right.

What is testimony?

Philosophers use the term ‘testimony’ to refer to any situation in which you believe something on the basis of what someone else asserts, either verbally or in writing. Hume and other philosophers writing about testimony are keen to point out: a lot of what we believe about the world is based on the testimony of other people. As Hume put it in the essay on miracles:

“there is no species of reasoning more common, more useful, and even necessary to human life, than that which is derived from the testimony of men.”

To understand what Hume is talking about, think of some city that you’ve never visited. You’ve got a lot of beliefs about that city: beliefs about who lives there, population size, what it’s like. All these beliefs are based on testimony: they are based on what you’ve read in newspapers about that city, or you’ve talked to someone who has been there, or you’ve read the Wikipedia article about it.

Hume assumes that you should only trust testimony when you have evidence that the testifier is likely to be right. Hume thinks that this assumption follows from what seems like an innocuous assumption, sometimes called evidentialism:

“A wise man … proportions his belief to the evidence.”

Hume argues that you need independent evidence to trust someone’s testimony, the credit we give testimony “admits of a diminution, greater or less, in proportion as the fact is more or less unusual.”

Hume’s definition of Miracle: A miracle is a violation of the laws of nature. I.e. something that has never happened “in the common course of nature.” For Hume, a miracle is an event that is an exception to a previously exception less regularity. It’s just something that has never happened before.

With this definition of a miracle in place, and with Hume’s assumption about testimony, we can now start to see why Hume concludes that you should never believe that a miracle has occurred, on the basis of testimony. Here’s how Hume articulates his argument in the essay on miracles:

“No testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle, unless the testimony be of such a kind, that its falsehood would be more miraculous, than the fact, which it endeavours to establish.”

That is, a miracle can only be credible if the testimony in its favour is far more forceful than the laws of nature contradicting it.

Hume’s last premise is that it is always more likely that the testimony of others is false than that it is true. False testimony is very common and it is more likely that people are wrong about things and so their sincere testimony is mistaken. Therefore, Hume concludes, you shouldn’t trust someone’s testimony, if what they’re claiming is that a miracle occurred.

Reid’s challenge:

Hume’s contemporary critic, Thomas Reid, challenged his assumption about testimony. The assumption Hume makes about testimony is that you should only trust testimony when you have evidence that the testifier is likely to be right. Reid argued that trusting testimony is similar to trusting your senses. Believing something, on the basis of what someone else says is just like believing something on the basis of seeing it with your own eyes. We don’t only trust our senses when we have evidence that they’re likely to be right. Reid challenges Hume’s assumption that we should only trust testimony on the basis of evidence that the testifier is likely to be right. So if Reid’s argument is right, Hume’s assumption about testimony is false.

Hume and Reid both believed that there were innate principles that governed how we think and how we feel. Reid, however, thought that we were also hardwired to trust other people’s testimony. He thought we had an innate “principle of credulity,” which he defined as:

“a disposition to confide in the veracity of others, and to believe what they tell us.”

For Reid, we are innately “hardwired” to trust other people’s testimony. For Hume, we first have to get evidence that they’re likely to be right – at least evidence that human beings in generally are likely to be right – before we can trust other people’s testimony. Reid asks us to think about small children and the extent to which they trust the testimony of other people. And he points out that children are very much disposed to trust the testimony of other people – they’ll believe whatever you tell them. But this, Reid argues, is incompatible with Hume’s picture of testimony:

“[I]f credulity were the effect of reasoning and experience [as Hume claims], it must grow up and gather strength, in the same proportion as reason and experience do. But, if it is the gift of Nature, it will be strongest in children, and limited and restrained by experience; and the most superficial view of human life shews, that the last is really the case, and not the first.”

In other words, if Hume’s picture were right, the principle of credulity would be weakest in children, because they’d not yet have any experience of how likely (or unlikely) people are to asserts truths (or falsehoods). But in fact children are the most trusting, and adults the least trusting and the most sceptical. This is the opposite of what you’d expect, if Hume’s picture were right. So rather than being based on experience, our trust in each other’s testimony is a “gift of Nature.”

Reid talks about what children do in fact believe, whereas Hume talks about what people ought to believe. But we can still appreciate Reid’s point here if we take him to be saying: Hume’s view implies that children should not trust the testimony of other people, until they have evidence that people are likely to assert the truth. But this seems wrong: there’s nothing wrong with children trusting the testimony of other people, like their parents. Reid claims, if we abided by Hume’s principles: If Hume were right,

“no proposition that is uttered in discourse would be believed [, and] such distrust and incredulity would deprive us of the greatest benefits of society, and place us in a worse condition than that of the savages.”

The big dispute between Hume and Reid on testimony: is trusting other people an innate principle (as Reid argues), or do we need evidence of the reliability of testimony before we trust it (as Hume argues)? In addition to the principle of credulity, Reid said that there was a “principle of veracity”, which he defined as: “a propensity to speak the truth … so as to convey our real sentiments.”

“Lying,” Reid goes on to say, “is doing violence to our nature.” For Reid, just as we are naturally trusting creatures, we are naturally honest creatures. Hume however challenges this idea that we are “hardwired” for honesty. He gives numerous examples of people testifying falsely. People often have motives to lie, as when “they have an interest in what they affirm.” There are “advantages” to “starting an imposture among an ignorant people.” Hume also says, Human beings are prone to believe “the tales of travellers” because human beings generally find the feelings of “surprise and wonder” agreeable. Hume says that human beings are prone to testify, regardless of whether they have good evidence for what they’re saying, because of

“[t]he pleasure of telling a piece of news so interesting, of propagating it, and of being the first reporters of it.” This, Hume argued, is why gossip and rumour spread so quickly.

What is Enlightenment?

Enlightenment, according to Immanuel Kant, is man’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s own understanding without the guidance of another. This immaturity is self-imposed when its cause lies not in lack of understanding, but in lack of resolve and courage to use it without guidance from another. ‘Sapere Aude!’ [Dare to know] ‘Have courage to use your own understanding!’–that is the motto of enlightenment.” According to Kant, Enlightenment is the process by which people could rid themselves of intellectual bondage and this could be achieved by thinking freely and using one’s self determinism to act judiciously.

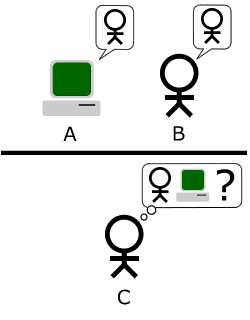

Kant is talking here about the extent to which we form beliefs or opinions on the basis of testimony. To believe something on the basis of testimony is to allow one’s “understanding” to be “guided” by another person. And Kant clearly thinks that not being so guided, not basing beliefs on testimony, is in some sense a virtue – hence the motto “Think for yourself.” Contemporary philosophers have come to call this virtue, if indeed it is a virtue, intellectual autonomy.

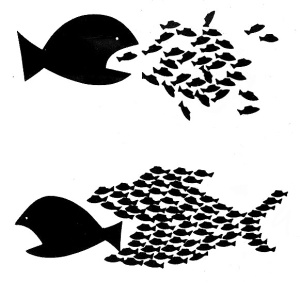

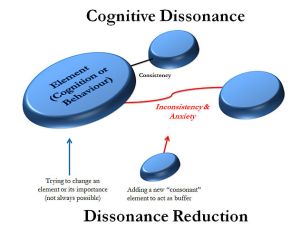

Hume’s approach to testimony is that we shouldn’t believe other’s testimony unless we have evidence that it is likely to be right. Hume doesn’t think that we should never believe something on the basis of their testimony. He thinks that we often do have enough evidence to trust other people’s testimony. We should only trust other’s people’s testimony, on his view, when we ourselves have evidence that the person is likely to be right. According to Hume we shouldn’t trust anyone blindly. According to Reid, intellectual autonomy is a violation of nature as humans are essentially trusting beings and social creatures and our beliefs and opinions are naturally guided by others. For Reid, instead of intellectual autonomy the virtue is intellectual solidarity. That is the ideal that Reid offers as against the individualism of Kant and Hume’s “enlightenment.”

Value of intellectual autonomy

Which theory is right? Hume and Kant with their ideal of intellectual autonomy or Reid with his ideal of intellectual solidarity? Why think that it is a good thing to be intellectually autonomous?

Kant appeals to “Sapre aude” which means “dare to be wise”. He argues that a person whose beliefs and opinions are based on testimony alone doesn’t really have knowledge. When he says “Dare to know” he means that dare to base your beliefs on the basis of something other than testimony.

Genuine or real knowledge requires what Plato called the ability to “give an account”: the ability to explain, or to situate that knowledge in some broader body of information. That is something, you might think, that you cannot get from testimony. That kind of understanding, or as Kant might put it wisdom can only be gotten on your own: you cannot get it from someone else. Perhaps the value of intellectual autonomy comes from the fact that knowledge (or understanding, or wisdom) is only possible for the intellectually autonomous person.

The second way to defend the value of intellectual autonomy is to think about the social or political implications of intellectual solidarity. The policy of trusting other people’s testimony, without evidence of their reliability, has conservative implications. Think of the extent to which our beliefs and opinions can be shaped by our communities, and in particular the communities that we grow up in. People tend to believe what the people around them believe, and they often inherit religious and political and moral views from previous generations. Our question about the value of intellectual autonomy can be seen as a question about the value of this tendency: are we fans of this tendency to trust other people (like Reid, with his views of the naturalness of trusting testimony), or are we sceptical of this tendency (like Hume)?

How you answer this question depends on how we think about conservatism in intellectual matters. If you value progressive and innovative breaks with tradition, and hope that conventional wisdom will be overturned, you may side with Hume, and see intellectual autonomy as a virtue – a social or political virtue. If you value the conservation of your community’s beliefs, and hope to avoid radical breaks with tradition, you may side with Reid, and see intellectual solidarity as a virtue.